While reading Allen Drury’s novel Anna Hastings, I couldn’t help thinking of Helen Thomas, the longtime United Press International correspondent. A fixture at White House news conferences for many decades, she was known for asking blunt, intimidating questions at a time when the Presidential press corps was almost exclusively male.

I don’t know whether Allen Drury had Thomas in mind when he produced Anna Hastings in 1977. The title character certainly possesses much of Thomas’s ambition. From humble beginnings, Anna rises to become one of Washington’s most influential journalists, marries a wealthy Senator and establishes her own newspaper. Ultimately, her iron will and self-righteousness bring her into conflict with the nation’s most powerful leaders, her own family and her best friends.

don’t know whether Allen Drury had Thomas in mind when he produced Anna Hastings in 1977. The title character certainly possesses much of Thomas’s ambition. From humble beginnings, Anna rises to become one of Washington’s most influential journalists, marries a wealthy Senator and establishes her own newspaper. Ultimately, her iron will and self-righteousness bring her into conflict with the nation’s most powerful leaders, her own family and her best friends.

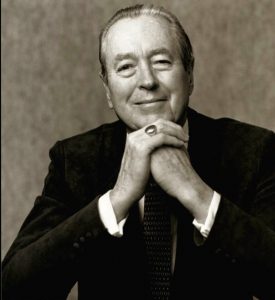

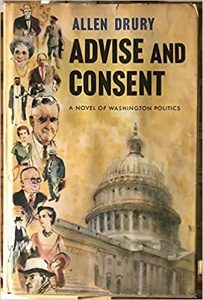

Drury’s first novel, Advise and Consent, appeared in 1959 and won the Pulitzer Prize. Though dated in some ways, it remains an intriguing exploration of American politics. For a fuller report on its impact on American readers and upon Congress itself , I recommend you check out Ken Ringle’s excellent perspective at the following link:

, I recommend you check out Ken Ringle’s excellent perspective at the following link:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/campaigns/junkie/links/drury2.htm

Because Anna Hastings deals with journalism, a favorite topic of mine, I decided to check it out. Regrettably, it does not achieve the high standard Drury set with Advise and Consent. We learn little about the daily grind of a reporter’s life. Instead, Anna uses beauty and charm to worm her way into the halls of Washington influence. A contradiction of idealism and ruthlessness, Anna doesn’t hesitate to step on anyone who gets in her way, including old colleagues who, inexplicably, remain loyal to her.

The best feature of this novel is how it puts the American news media on trial. Anna betrays the standards of objectivity that once defined reportorial excellence, using her newspaper as a weapon against those who do not share her opinions on the issues of the day. As the author puts it: “Partisanship, vindictiveness, personal antipathies, deliberate slanting, deliberate suppression of opposing viewpoints … all these now masquerade with a bland self-righteousness as honesty, lack of bias, fairness, compassion and objectivity.”

Don’t we see these infections even now in our daily news buffets?

Overall, I found Anna Hastings a disappointment. It also contains a great deal of foul language and profanity that were absent from Drury’s 1959 novel. If you’re looking for a good political thriller, I recommend Advise and Consent.